Lactose intolerance: Difference between revisions

imported>Elizabeth Sarah McClure No edit summary |

imported>Mary Ash No edit summary |

||

| (44 intermediate revisions by 6 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{subpages}} | {{subpages}} | ||

{{EZarticle}} | {{EZarticle}} | ||

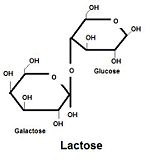

{{Image|lactose.JPG|right|150px|A lactose molecule.}} | |||

'''Lactose intolerance''' is "the condition resulting from the absence or deficiency of lactase in the mucosa cells of the [[gastrointestinal tract]], and the inability to break down [[lactose]] in milk for [[absorption]]. Bacterial fermentation of the unabsorbed lactose leads to symptoms that range from a mild indigestion ([[dyspepsia]]) to severe [[diarrhea]]. Lactose intolerance may be an inborn error or acquired."<ref>{{MeSH}}</ref> | |||

Lactase is normally produced in the cells lining the small intestine and is required to break down the [[disaccharide]] lactose to the usable sugars, [[glucose]] and [[galactose]]. The loss of this function means that lactose, the major sugar in milk, cannot be broken down or [[metabolize]]d in the gut. Consequently, milk product cannot be digested by people who are lactose intolerant but the [[enteral bacteria]] adapt and ferment the sugar in the intestines, often leading to bloating and gas symptoms.<ref>{{Cite book | edition = 7 | pages = 70-71 | last = Campbell | first = N.A. | coauthors = J.B. Reece | |||

| edition = 7 | | title = Biology | publication = Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data | date = 2005 | ||

| pages = 70-71 | }}</ref> Lactose intolerance is often referred to as lactase nonpersistence or lactase restriction since it is due to the lack of the lactase enzyme. | ||

| last = Campbell | |||

| first = N.A. | |||

| coauthors = J.B. Reece | |||

| title = Biology | |||

| publication = Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data | |||

| date = 2005 | |||

}}</ref> | |||

Population studies suggest that the most common form of lactase intolerance is the ancestral state for humans<ref name=Wiley2004>{{Cite journal | volume = 106 | issue = 3 | pages = 506-517 | last = Wiley | first = Andrea S. | title = "Drink Milk for Fitness": The Cultural Politics of Human Biological Variation and Milk Consumption in the United States | journal = American Anthropologist | |||

| date = September 2004 }}</ref>; lactase is expressed during childhood but the activity decreases into adulthood. It is thought that new mutations led to variants of the lactase [[gene]] that remain switched on into adulthood. This is called lactase persistence and such variants are now abundant in populations that historically led a pastoral lifestyle, probably due to selective pressure for the new [[allele]]s. | |||

__TOC__ | __TOC__ | ||

== | == Classification == | ||

Lactose intolerance is not the same as a milk allergy, which is a negative immune response to milk proteins. | |||

=== Primary Lactose Intolerance === | === Primary Lactose Intolerance === | ||

Primary lactose intolerance is caused by genetic and environmental factors and occurs in adulthood. It occurs in populations where dairy products are not commonly available or consumed or have not been consumed for several generations. The [[allele]] that expresses the lactose intolerance [[phenotype]] (as the decline in the ability to produce [[lactase]]) is [[recessive]]. | |||

Primary lactose intolerance caused by genetic and environmental factors. It occurs in populations where dairy products are not commonly available or consumed. The [[allele]] that | |||

=== Secondary Lactose Intolerance === | === Secondary Lactose Intolerance === | ||

Secondary lactose intolerance is also caused by environmental factors. It is often temporary and is a result of many gastrointestinal diseases from parasites or other causes. | Secondary lactose intolerance is also caused by environmental factors. It is often temporary and is a result of many gastrointestinal diseases from parasites or other causes. It can also be caused by [[infant colic]], which damages the vili that produce lactase in the small intestine.<ref>{{Cite journal | ||

| volume = 14 | |||

| issue = 5 | |||

| pages = 359-363 | |||

| last = Kanabar | |||

| first = D. | |||

| coauthors = M. Randhawa, P. Clayton | |||

| title = Improvement of Symptoms in Infant Colic Following Reduction of Lactose Load with Lactase | |||

| journal = FASEB Journal | |||

| date = October 2001 | |||

}}</ref> | |||

=== Congenital Lactase Deficiency === | === Congenital Lactase Deficiency === | ||

Congenital Lactase Deficiency is present at birth. It is an [[autosomal]] [[recessive]] genetic disorder that | Congenital Lactase Deficiency is present at birth and is the rarest form of lactose intolerance. It is an [[autosomal]] [[recessive]] genetic disorder caused by a mutation on the gene that produces lactase.<ref>{{Cite journal | ||

| volume = 5 | | volume = 5 | ||

| issue = 3 | | issue = 3 | ||

| Line 54: | Line 46: | ||

}}</ref> | }}</ref> | ||

==Epidemiology== | |||

== | Table 1.1 Frequency of Adult Lactose Intolerance within Population Groups <ref name=Jurmain2005 /> | ||

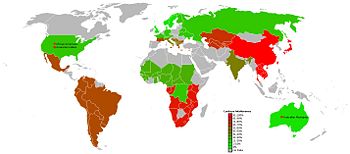

[[Image:LacIntol-World2.JPG|right|thumb|350px|{{#ifexist:Template:LacIntol-World2.JPG/credit|{{lactose.JPG/credit}}<br/>|}}Global distribution of lactose intolerance.]] | |||

| | |||

| | |||

| | |||

| | |||

}}</ | |||

{| class="wikitable" | {| class="wikitable" | ||

|- | |- | ||

! Population Group | ! Population Group | ||

! Percent | ! Percent | ||

|- | |- | ||

| United States Whites | | United States Whites | ||

| Line 104: | Line 66: | ||

| 4 | | 4 | ||

|- | |- | ||

| United States Blacks | | United States Blacks | ||

| 70-77 | | 70-77 | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Line 122: | Line 84: | ||

| 99 | | 99 | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Asian Americans | | Asian Americans | ||

| 95-100 | | 95-100 | ||

|- | |||

| United States Jews | |||

| 69 | |||

|- | |- | ||

| Native Australians | | Native Australians | ||

| 85 | | 85 | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Native Americans | | Native Americans | ||

| 99 | | 99 | ||

|} <ref>{{Cite book | |} | ||

| edition = 10 | |||

| pages = 416-419 | Because most adult Americans of Western European descent exhibit lactase persistence, it is commonly assumed that it is the most common gene expression. As shown in Table 1.1, however, United States Whites are one of few population groups that show high levels of lactase persistence. Lactase persistence is only common in adults with ancestry in pastoral populations. This is supported by the low levels of lactose intolerance in the United States Whites and the African Fulani and Tutsi populations. The ancestry of a large percentage of United States Whites is in Western Europe, where pastoralism was a common means of sustenance. The nomadic Fulani tribe of East, Central, and West Africa and the Tutsi tribe of Rwanda and Burundi are two populations in Africa that, unlike most other African populations, have a history of pastoralism.<ref>{{Cite journal | ||

| volume = 66 | |||

| issue = 4 | |||

| part = 1 | |||

| pages = 944-947 | |||

| last = Flannery | |||

| first = Kent V. | |||

| title = Man and Cattle: Proceedings of a Symposium on Domestication | |||

| journal = American Anthropologist | |||

| date = August 1964 | |||

}}</ref> Because of this, they are among the few populations of African descent that evolved independently to genetically favor lactose tolerance. | |||

=== Geographic Variance === | |||

Lactose intolerance is possibly an example of [[biocultural evolution]], human variation through multiple generations due to both biological and cultural forces. Lactose intolerance is inherited as the expression of the [[recessive gene]]. However, expression of the trait is also environmentally determined. [[Enteral bacteria]] can often buffer the effects of lactose intolerance and can be increased with previous exposure, leading to acquired tolerance even in individuals are genetically lactose intolerant. | |||

Variance throughout populations is most likely due to a history of an economic reliance on pastoralism and, which results in the increased consumption of milk after childhood. Historically, the availabiliy of milk had disappeared after weaning. This rendered [[lactase]] useless and perhaps problematic for the digestion of other foods in humans. Therefore, there was a possible [[genetic advantage]] to ceasing the production of [[lactase]]. This would change the [[allele frequency]] making the expression of lactose intolerance genetically dominant. In populations with a history of pastoralism, however, there was a likely genetic advantage or [[allele]] shift toward lactose tolerance. The descendants of these populations, most European groups, tend to retain lactose tolerance. Distribution of lactose intolerance in [[Africa]] seems to be due to the same variation in economic history. Most populations of [[Africa]] exhibit lactose intolerance. However, individuals in groups that historically relied on pastoralism, such as the [[Fulani]] and [[Tutsi]] of Africa, tend to show lactose tolerance. <ref name=Jurmain2005>{{Cite book | |||

| edition = 10 | |||

| pages = 416-419 | |||

| last = Jurmain | | last = Jurmain | ||

| first = Robert | | first = Robert | ||

| coauthors = Lynn Kilgore, Wenda Trevathan | | coauthors = Lynn Kilgore, Wenda Trevathan | ||

| title = Introduction to Physical Anthropology | | title = Introduction to Physical Anthropology | ||

| publication = Thomson Learning, Inc | | publication = Thomson Learning, Inc | ||

| date = 2005 | | date = 2005 | ||

}}</ref> | }}</ref> | ||

==References== | Another theory about the ability of people of Northern European descent has to do with [[vitamin D]]. Because the allele that expresses in the lactose tolerance [[phenotype]] or continued [[lactase]] production in adulthood is [[recessive]], selective forces keep it in existence. As mentioned previously, one selective force is the necessity of [[lactose]] consumption in pastoral communities. Another in Northern [[Europe]] is the reduced production of [[vitamin D]] due to the lack of direct sunlight in the region. The lack of [[vitamin D]] would make the population more vulnerable to bone diseases like [[rickets]] because of the poor absorption of calcium. The advantage of continued [[lactase]] production is the ability to consume milk after childhood. Milk contains high levels of calcium, which would help to counter the [[vitamin D]] deficiency. This theory has gained support because of its congruence with the theory that Northern European light skin color allows the most [[vitamin D]] production with little sunlight. <ref>{{Cite journal | ||

| volume = 4 | |||

| issue = 5 | |||

| pages = 76-81 | |||

| last = Patterson | |||

| first = K.D. | |||

| title = Lactose intolerance | |||

| journal = The Cambridge World History of Food | |||

| publication = Cambridge University Press | |||

| date = 1997 | |||

}}</ref> However, this theory is not relevant south of the equator, nor is it supported with archaeological or osteological evidence. | |||

Lactase persistence is sometimes seen in groups that frequently consume dairy because they usually consume it as cheese or yogurt, forms in which bacterial action has already broken down the [[lactose]]. | |||

==Etiology / cause== | |||

=== Related Foods === | |||

==== Dairy Products ==== | |||

Dairy products tend to contain higher levels of lactose in the liquid components versus the fat components. Therefore, lower fat dairy products and those that have not been processed as much, such as whole milk, tend to have more lactose. Fermented dairy products tend to have more fat and lactose, such as yogurt or sourcream. Consumption of dairy products is recommended for the calcium they contain. | |||

==== Nondairy Products ==== | |||

Lactose is often added into medications or foods like bread, margarine, and processed meat. While dairy products are recommended for calcium consumption, there are some lactose-free nondairy products that contain high levels of calcium, such as green leafy vegetables, fish, and legumes.<ref name=Cohen1997>{{Cite book | |||

| pages = 189-270 | |||

| last = Cohen | |||

| first = Robert | |||

| title = Milk: The Deadly Poison | |||

| publication = Argus Publishing | |||

| publication location = Englewood Cliffs, NJ | |||

| date = 1997 | |||

}}</ref> Many nondairy foods are also fortified with calcium such as orange juice, cereal, and many dairy substitutes made with rice or soy. | |||

=== Genetic Factors === | |||

Lactose intolerance is an [[autosomal recessive trait]]. The allele variations differ in the temporal aspect of their expression. The dominant allele is expressed later and, therefore, the [[phenotype]] for the [[dominant allele]] is the persistence of production of the lactase enzyme. The recessive allele is expressed only early in life and results in lactose intolerance. The gene that codes for the lactase enzyme is located on [[chromosome]] 2. This is the case in all populations, but the reguation of the gene varies. The lactase gene has four common [[haplotypes]]- A, B, C, and U. The A haplotype is usually found in populations that exhibit lactase persistence. Increased haplotype diversity occurs in populations that exhibit lactose intolerance. The expression of the lactase persistence [[phenotype]] gives genetic advantage to members of populations that consume milk. This is why most express the [[dominant allele]] in milk consuming populations. While it is still unclear, it is likely that lactase regulation occurs during [[DNA]] [[transcription]] because there is variation in [[mRNA]] levels between lactase persistent and impersistent individuals. <ref name=Wiley2004 /> Genetic drift probably also played a role in latase gene diversity. The more homogeneous populations are probably as such because of genetic drift, this is why African cultures have more diversity in the haplotypes. Gene flow, mainly due to colonization, is probably the cause of continued frequencies of lactose intolerance and tolerance within populations. Lactose tolerance is rare in a worldwide sense, but it exists in scattered populations that have no contact. As shown by the low levels of lactose intolerance in United States Whites and the Fulani and Tutsi tribes, the genes evolved independently in different populations around the world. | |||

== Symptoms == | |||

Nausea, bloating, cramps, diarrhea, and gas are symptoms commonly experienced with lactose intolerance. They typically occur 30 to 120 minutes after consuming [[lactose]].<ref name="pmid17599979">{{cite journal| author=Bhatnagar S, Aggarwal R| title=Lactose intolerance. | journal=BMJ | year= 2007 | volume= 334 | issue= 7608 | pages= 1331-2 | pmid=17599979 | |||

| url=http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/elink.fcgi?dbfrom=pubmed&tool=clinical.uthscsa.edu/cite&retmode=ref&cmd=prlinks&id=17599979 | doi=10.1136/bmj.39252.524375.80 }} </ref> | |||

== Sociopolitical Issues == | |||

While the American dairy industry holds that the frequency of lactose intolerance is overestimated, recent research in gastrointestinal problems shows that it is likely underdiagnosed in the United States.<ref name=Wiley2007>{{Cite journal | |||

| volume = 109 | |||

| issue = 4 | |||

| pages = 666-677 | |||

| last = Wiley | |||

| first = Andrea S. | |||

| title = Transforming Milk in a Global Economy | |||

| journal = American Anthropologist | |||

| date = November 2007 | |||

}}</ref> It has also been argued that despite its depiction as a "perfect food" by the dairy industry and government funded health organizations, milk is in fact bad for the health of all adults due to added hormones and biological defects in many farmed dairy cows. <ref name=Cohen1997 /> Still, government supported medical associations advocate the consumption of 2 to 3 servings of dairy daily as a source of calcium. Also, it is typically recommended that those who experience symptoms of lactose intolerance test the amount of dairy they can consume without experiencing negative effects. This is funded and widely accepted information despite the high incidence of lactose intolerance (as it is the more common expression of genes worldwide) and the many foods that contain calcium without lactose (for example, leafy greens).<ref name=Wiley2007 /> | |||

==Treatment== | |||

Most patients can tolerate 12 to 15 g of lactose.<ref name="pmid20404262">{{cite journal| author=Shaukat A, Levitt MD, Taylor BC, Macdonald R, Shamliyan TA, Kane RL et al.| title=Systematic Review: Effective Management Strategies for Lactose Intolerance. | journal=Ann Intern Med | year= 2010 | volume= | issue= | pages= | pmid=20404262 | |||

| url=http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/elink.fcgi?dbfrom=pubmed&tool=clinical.uthscsa.edu/cite&retmode=ref&cmd=prlinks&id=20404262 | doi=10.1059/0003-4819-152-12-201006150-00241 }} </ref> | |||

==Lactose Content of Selected Dairy Products== | |||

1 cup whole, reduced fat or nonfat milk 11 grams; 1 cup chocolate milk 11 grams; 1 cup buttermilk 10 grams; 1/2 cup ice cream 6 grams; 1/2 cup sherbet 2 grams; 1 cup low fat yogurt 5 grams; 1/2 cup creamed cottage cheese 3 grams.<ref name="urlwww.healthsystem.virginia.edu">{{cite web | |||

|url=http://www.healthsystem.virginia.edu/internet/digestive-health/nutrition/lactosecontent.pdf | |||

|title=www.healthsystem.virginia.edu | |||

|format= | |||

|work= | |||

|accessdate=2010-10-26 | |||

}}</ref> | |||

== References == | |||

<references/> | <references/> | ||

Revision as of 21:08, 26 October 2010

Lactose intolerance is "the condition resulting from the absence or deficiency of lactase in the mucosa cells of the gastrointestinal tract, and the inability to break down lactose in milk for absorption. Bacterial fermentation of the unabsorbed lactose leads to symptoms that range from a mild indigestion (dyspepsia) to severe diarrhea. Lactose intolerance may be an inborn error or acquired."[1]

Lactase is normally produced in the cells lining the small intestine and is required to break down the disaccharide lactose to the usable sugars, glucose and galactose. The loss of this function means that lactose, the major sugar in milk, cannot be broken down or metabolized in the gut. Consequently, milk product cannot be digested by people who are lactose intolerant but the enteral bacteria adapt and ferment the sugar in the intestines, often leading to bloating and gas symptoms.[2] Lactose intolerance is often referred to as lactase nonpersistence or lactase restriction since it is due to the lack of the lactase enzyme.

Population studies suggest that the most common form of lactase intolerance is the ancestral state for humans[3]; lactase is expressed during childhood but the activity decreases into adulthood. It is thought that new mutations led to variants of the lactase gene that remain switched on into adulthood. This is called lactase persistence and such variants are now abundant in populations that historically led a pastoral lifestyle, probably due to selective pressure for the new alleles.

Classification

Lactose intolerance is not the same as a milk allergy, which is a negative immune response to milk proteins.

Primary Lactose Intolerance

Primary lactose intolerance is caused by genetic and environmental factors and occurs in adulthood. It occurs in populations where dairy products are not commonly available or consumed or have not been consumed for several generations. The allele that expresses the lactose intolerance phenotype (as the decline in the ability to produce lactase) is recessive.

Secondary Lactose Intolerance

Secondary lactose intolerance is also caused by environmental factors. It is often temporary and is a result of many gastrointestinal diseases from parasites or other causes. It can also be caused by infant colic, which damages the vili that produce lactase in the small intestine.[4]

Congenital Lactase Deficiency

Congenital Lactase Deficiency is present at birth and is the rarest form of lactose intolerance. It is an autosomal recessive genetic disorder caused by a mutation on the gene that produces lactase.[5]

Epidemiology

Table 1.1 Frequency of Adult Lactose Intolerance within Population Groups [6]

| Population Group | Percent |

|---|---|

| United States Whites | 2-19 |

| Finnish | 18 |

| Swiss | 12 |

| Swedish | 4 |

| United States Blacks | 70-77 |

| Ibos | 99 |

| Bantu | 90 |

| Fulani | 22 |

| Tutsi | 7 |

| Thais | 99 |

| Asian Americans | 95-100 |

| United States Jews | 69 |

| Native Australians | 85 |

| Native Americans | 99 |

Because most adult Americans of Western European descent exhibit lactase persistence, it is commonly assumed that it is the most common gene expression. As shown in Table 1.1, however, United States Whites are one of few population groups that show high levels of lactase persistence. Lactase persistence is only common in adults with ancestry in pastoral populations. This is supported by the low levels of lactose intolerance in the United States Whites and the African Fulani and Tutsi populations. The ancestry of a large percentage of United States Whites is in Western Europe, where pastoralism was a common means of sustenance. The nomadic Fulani tribe of East, Central, and West Africa and the Tutsi tribe of Rwanda and Burundi are two populations in Africa that, unlike most other African populations, have a history of pastoralism.[7] Because of this, they are among the few populations of African descent that evolved independently to genetically favor lactose tolerance.

Geographic Variance

Lactose intolerance is possibly an example of biocultural evolution, human variation through multiple generations due to both biological and cultural forces. Lactose intolerance is inherited as the expression of the recessive gene. However, expression of the trait is also environmentally determined. Enteral bacteria can often buffer the effects of lactose intolerance and can be increased with previous exposure, leading to acquired tolerance even in individuals are genetically lactose intolerant.

Variance throughout populations is most likely due to a history of an economic reliance on pastoralism and, which results in the increased consumption of milk after childhood. Historically, the availabiliy of milk had disappeared after weaning. This rendered lactase useless and perhaps problematic for the digestion of other foods in humans. Therefore, there was a possible genetic advantage to ceasing the production of lactase. This would change the allele frequency making the expression of lactose intolerance genetically dominant. In populations with a history of pastoralism, however, there was a likely genetic advantage or allele shift toward lactose tolerance. The descendants of these populations, most European groups, tend to retain lactose tolerance. Distribution of lactose intolerance in Africa seems to be due to the same variation in economic history. Most populations of Africa exhibit lactose intolerance. However, individuals in groups that historically relied on pastoralism, such as the Fulani and Tutsi of Africa, tend to show lactose tolerance. [6]

Another theory about the ability of people of Northern European descent has to do with vitamin D. Because the allele that expresses in the lactose tolerance phenotype or continued lactase production in adulthood is recessive, selective forces keep it in existence. As mentioned previously, one selective force is the necessity of lactose consumption in pastoral communities. Another in Northern Europe is the reduced production of vitamin D due to the lack of direct sunlight in the region. The lack of vitamin D would make the population more vulnerable to bone diseases like rickets because of the poor absorption of calcium. The advantage of continued lactase production is the ability to consume milk after childhood. Milk contains high levels of calcium, which would help to counter the vitamin D deficiency. This theory has gained support because of its congruence with the theory that Northern European light skin color allows the most vitamin D production with little sunlight. [8] However, this theory is not relevant south of the equator, nor is it supported with archaeological or osteological evidence.

Lactase persistence is sometimes seen in groups that frequently consume dairy because they usually consume it as cheese or yogurt, forms in which bacterial action has already broken down the lactose.

Etiology / cause

Related Foods

Dairy Products

Dairy products tend to contain higher levels of lactose in the liquid components versus the fat components. Therefore, lower fat dairy products and those that have not been processed as much, such as whole milk, tend to have more lactose. Fermented dairy products tend to have more fat and lactose, such as yogurt or sourcream. Consumption of dairy products is recommended for the calcium they contain.

Nondairy Products

Lactose is often added into medications or foods like bread, margarine, and processed meat. While dairy products are recommended for calcium consumption, there are some lactose-free nondairy products that contain high levels of calcium, such as green leafy vegetables, fish, and legumes.[9] Many nondairy foods are also fortified with calcium such as orange juice, cereal, and many dairy substitutes made with rice or soy.

Genetic Factors

Lactose intolerance is an autosomal recessive trait. The allele variations differ in the temporal aspect of their expression. The dominant allele is expressed later and, therefore, the phenotype for the dominant allele is the persistence of production of the lactase enzyme. The recessive allele is expressed only early in life and results in lactose intolerance. The gene that codes for the lactase enzyme is located on chromosome 2. This is the case in all populations, but the reguation of the gene varies. The lactase gene has four common haplotypes- A, B, C, and U. The A haplotype is usually found in populations that exhibit lactase persistence. Increased haplotype diversity occurs in populations that exhibit lactose intolerance. The expression of the lactase persistence phenotype gives genetic advantage to members of populations that consume milk. This is why most express the dominant allele in milk consuming populations. While it is still unclear, it is likely that lactase regulation occurs during DNA transcription because there is variation in mRNA levels between lactase persistent and impersistent individuals. [3] Genetic drift probably also played a role in latase gene diversity. The more homogeneous populations are probably as such because of genetic drift, this is why African cultures have more diversity in the haplotypes. Gene flow, mainly due to colonization, is probably the cause of continued frequencies of lactose intolerance and tolerance within populations. Lactose tolerance is rare in a worldwide sense, but it exists in scattered populations that have no contact. As shown by the low levels of lactose intolerance in United States Whites and the Fulani and Tutsi tribes, the genes evolved independently in different populations around the world.

Symptoms

Nausea, bloating, cramps, diarrhea, and gas are symptoms commonly experienced with lactose intolerance. They typically occur 30 to 120 minutes after consuming lactose.[10]

Sociopolitical Issues

While the American dairy industry holds that the frequency of lactose intolerance is overestimated, recent research in gastrointestinal problems shows that it is likely underdiagnosed in the United States.[11] It has also been argued that despite its depiction as a "perfect food" by the dairy industry and government funded health organizations, milk is in fact bad for the health of all adults due to added hormones and biological defects in many farmed dairy cows. [9] Still, government supported medical associations advocate the consumption of 2 to 3 servings of dairy daily as a source of calcium. Also, it is typically recommended that those who experience symptoms of lactose intolerance test the amount of dairy they can consume without experiencing negative effects. This is funded and widely accepted information despite the high incidence of lactose intolerance (as it is the more common expression of genes worldwide) and the many foods that contain calcium without lactose (for example, leafy greens).[11]

Treatment

Most patients can tolerate 12 to 15 g of lactose.[12]

Lactose Content of Selected Dairy Products

1 cup whole, reduced fat or nonfat milk 11 grams; 1 cup chocolate milk 11 grams; 1 cup buttermilk 10 grams; 1/2 cup ice cream 6 grams; 1/2 cup sherbet 2 grams; 1 cup low fat yogurt 5 grams; 1/2 cup creamed cottage cheese 3 grams.[13]

References

- ↑ Anonymous (2024), Lactose intolerance (English). Medical Subject Headings. U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ↑ Campbell, N.A.; J.B. Reece (2005). Biology, 7, 70-71.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Wiley, Andrea S. (September 2004). ""Drink Milk for Fitness": The Cultural Politics of Human Biological Variation and Milk Consumption in the United States". American Anthropologist 106 (3): 506-517.

- ↑ Kanabar, D.; M. Randhawa, P. Clayton (October 2001). "Improvement of Symptoms in Infant Colic Following Reduction of Lactose Load with Lactase". FASEB Journal 14 (5): 359-363.

- ↑ Montgomery, R.K.; H.A. Buller, E.H Rings., R.J Grand (1991). "Lactose intolerance and the genetic regulation of intestinal lactase- phlorizin hydrolase". FASEB Journal 5 (3): 70-73.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Jurmain, Robert; Lynn Kilgore, Wenda Trevathan (2005). Introduction to Physical Anthropology, 10, 416-419.

- ↑ Flannery, Kent V. (August 1964). "Man and Cattle: Proceedings of a Symposium on Domestication". American Anthropologist 66 (4): 944-947.

- ↑ Patterson, K.D. (1997). "Lactose intolerance". The Cambridge World History of Food 4 (5): 76-81.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Cohen, Robert (1997). Milk: The Deadly Poison, 189-270.

- ↑ Bhatnagar S, Aggarwal R (2007). "Lactose intolerance.". BMJ 334 (7608): 1331-2. DOI:10.1136/bmj.39252.524375.80. PMID 17599979. Research Blogging.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Wiley, Andrea S. (November 2007). "Transforming Milk in a Global Economy". American Anthropologist 109 (4): 666-677.

- ↑ Shaukat A, Levitt MD, Taylor BC, Macdonald R, Shamliyan TA, Kane RL et al. (2010). "Systematic Review: Effective Management Strategies for Lactose Intolerance.". Ann Intern Med. DOI:10.1059/0003-4819-152-12-201006150-00241. PMID 20404262. Research Blogging.

- ↑ www.healthsystem.virginia.edu. Retrieved on 2010-10-26.