Dallas, Texas: Difference between revisions

imported>Richard Jensen (add history and bibl) |

imported>Richard Jensen (add text) |

||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

In 1841, two years after his first visit to stake a claim to the land on which Dallas now stands, John Neely Bryan, a Tennessee trader, returned to the then [[Republic of Texas]] and built a tiny one-room cabin, the first in Dallas. Ir remains one of the few historical landmarks preserved in the city, and has been moved to the front of the Dallas County Courthouse. Bryan, quick to see the advantages of the National Highway then being built toward his land, founded a village. In 1844 the village was laid out in lots 200 feet square. The only real clue as to the choice of the name for the village is a remark made by Bryan "I named it for my friend Dallas." Dallas County in 1846 was named after George Mifflin Dallas, the current vice-president of the United States. In 1852 Bryan sold his interest in the settlement to Alexander and Sarah Cockrell. | In 1841, two years after his first visit to stake a claim to the land on which Dallas now stands, John Neely Bryan, a Tennessee trader, returned to the then [[Republic of Texas]] and built a tiny one-room cabin, the first in Dallas. Ir remains one of the few historical landmarks preserved in the city, and has been moved to the front of the Dallas County Courthouse. Bryan, quick to see the advantages of the National Highway then being built toward his land, founded a village. In 1844 the village was laid out in lots 200 feet square. The only real clue as to the choice of the name for the village is a remark made by Bryan "I named it for my friend Dallas." Dallas County in 1846 was named after George Mifflin Dallas, the current vice-president of the United States. In 1852 Bryan sold his interest in the settlement to Alexander and Sarah Cockrell. | ||

Dallas was incorporated as a town in 1856. | Dallas was incorporated as a town in 1856 and became an important rtegional trading center. In 1856 several hundred Europeans, followers of the French social philosopher [[Charles Fourier]], attempted to set up a socialistic colony called "La Réunion" across the river from Dallas. The colony failed in 1858, and many of the colonists moved to Dallas, bringing with them a cosmopolitanism then lacking in most of the state. | ||

The town, almost completely destroyed by fire in July 1860, was rebuilt during the 1860s. Phillips (1999) explores the economic, political, ethnic, and regional tensions that caused an outbreak of mass white hysteria in response to an alleged slave rebellion that was held responsible for the great fire. The fire destroyed the entire downtown and incited numerous hangings and torture of white Union sympathizers and blacks falsely accused of arson by the majority of pro-slavery Texans, such as rabid Confederate editor Charles R. Pryor of the ''Dallas Herald''. These civil disturbances persisted despite pleas for justice by free-state whites living in Texas who hoped to minimize the vengeful mob mentality in the Dallas area. | |||

During the Civil War, Dallas was the quartermaster, commissary, and administrative headquarters for the Confederate Army, but no fighting occurred near the city. | |||

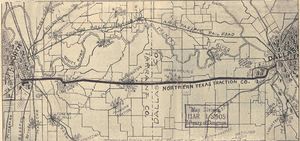

[[Image:Dallas-1905rr.jpg|thumb|450ppx|Dallas-Ft. Worth area in 1905]] | [[Image:Dallas-1905rr.jpg|thumb|450ppx|Dallas-Ft. Worth area in 1905]] | ||

Dallas was incorporated as a city in 1871 and grew rapidly during the 1870s as a railroad and distribution center for northeast Texas. In 1873, through a trick played on the legislature, the east-west Texas and Pacific Railroad was persuaded to cross at Dallas the Houston and Texas tracks, which were being built northward from the Gulf. The boom years brought on by the railroad in the 1870s greatly accelerated the growth of Dallas while exacerbating class and ethnic stratification among the city's population. | |||

By 1900 the city's population reached 38,000 and by 1930 it had risen to about 260,500. | |||

===Progressive era: 1890-1930=== | |||

[[Progressive Era]] reformers sought to improve municipal government by such changes as the commission system, city planning, and zoning controls. The interests of white business and residential districts were protected, but sometimes at the expense of blacks who lived in segregated neighborhoods.<ref>Patricia E. Gower, "The Price of Exclusion: Dallas Municipal Policy and its Impact on African Americans." ''East Texas Historical Journal'' 2001 39(1): 43-54. Issn: 0424-1444 </ref> Fairbanks (1999) explores the changing assumptions about city planning and government among the city's leaders. Dissatisfied with its haphazard development they endorsed centralized planning and wrote and secured the adoption of a new charter and set up a board of commissioners. The commission structure, however, caused government officials to view the city in separate parts rather than as a whole. By the 1920s supporters of comprehensive planning were calling for a program that included adoption of council-manager government, a citywide zoning policy, and public funds for improvements in parks, sewers, schools, and city streets. Voters approved the bond proposals and charter amendments in 1927 and 1930. Dallas thus achieved a more coordinated government which was theoretically more aware of the city's needs and more able to treat those needs equally for the benefit of the city as a whole. | |||

==Self image== | |||

The city's fathers originally depicted Dallas as southern in order to rationalize slavery and opposition to [[Reconstruction]], but this discouraged Northern investment and the political support of wealthy [[Yankee]] immigrants to the city. From the 1870s on, Dallas leaders portrayed the city as southwestern, or later as part of the "Sunbelt", in order to incorporate wealthy non-southern whites, including Jews, into society. For example, between 1852 and 1925 the seven Sanger brothers built successful mercantile businesses along developing railroad lines, including the Sanger Bros. department store, and occupied numerous city and state government posts.<ref>Rose G. Biderman, "The Sanger Brothers and Their Role in Texas History." ''Western States Jewish History'' 1996 28(2): 149-158. Issn: 0749-5471 </ref> White blue collar workers were marginalized, and even more so the Mexican Americans, and blacks.<ref> See Michael Phillips, ''White Metropolis: Race, Ethnicity, and Religion in Dallas, 1841-2001.'' (2006). </ref> | |||

==Gender== | |||

Women did much to establish the fundamental elements of the social structure of the city, focusing their energies on families, schools, and churches during the city's pioneer days. Many of the organizations which created a modern urban scene were founded and led by middle class women. Through voluntary organizations and club work, they connected their city to national cultural and social trends. By the 1880s women in temperance and suffrage movements shifted the boundaries between private and public life in Dallas by pushing their way into politics in the name of social issues.<ref> Elizabeth York Enstam, ''Women and the Creation of Urban Life: Dallas, Texas, 1843-1920.'' (1998). </ref> | |||

During 1913-19, advocates of woman suffrage drew on the educational and advertising techniques of the national parties and the lobbying tactics of the women's club movement. They also tapped into popular culture, successfully using popular symbolism and traditional ideals to adapt community festivals and social gatherings to the task of political persuasion. The Dallas Equal Suffrage Association developed a suffrage campaign based on social values and community standards. Community and social occasions served as recruiting opportunities for the suffrage cause, blunting its radical implications with the familiarity of customary events and dressing it in the values of traditional female behavior, especially propriety.<ref>Elizabeth York Enstam, "The Dallas Equal Suffrage Association, Political Style, and Popular Culture: Grassroots Strategies of the Woman Suffrage Movement, 1913-1919." ''Journal of Southern History'' 2002 68(4): 817-848. </ref> | |||

Women of color usually operated separately. Juanita Craft (1902-85) was a leader in the civil rights movement through the Dallas NAACP. She focused on working with black youths, organizing them as the vanguard in protests against segregation practices in Texas.<ref> Stefanie Decker, "Women in the Civil Rights Movement: Juanita Craft Versus the Dallas Elite." ''East Texas Historical Journal'' 2001 39(1): 33-42. Issn: 0424-1444 </ref> | |||

==Bibliography== | ==Bibliography== | ||

===Guides and popular history=== | |||

* Acheson, Sam Hanna. ''Dallas Yesterday,'' (1977) | * Acheson, Sam Hanna. ''Dallas Yesterday,'' (1977) | ||

* Buckner, Sharry. ''City Smart: Dallas/Ft. Worth'' (2000) [http://www.amazon.com/City-Smart-Dallas-Ft-Worth/dp/1562614339/ref=sr_1_9?ie=UTF8&s=books&qid=1213913472&sr=1-9 excerpt and text search] | * Buckner, Sharry. ''City Smart: Dallas/Ft. Worth'' (2000) [http://www.amazon.com/City-Smart-Dallas-Ft-Worth/dp/1562614339/ref=sr_1_9?ie=UTF8&s=books&qid=1213913472&sr=1-9 excerpt and text search] | ||

* Calvin, Peter A. ''Dallas, Texas: A Photographic Portrait'' (2007) [http://www.amazon.com/Dallas-Texas-Photographic-Peter-Calvin/dp/1885435754/ref=pd_bbs_sr_2?ie=UTF8&s=books&qid=1213913472&sr=1-2 excerpt and text search] | * Calvin, Peter A. ''Dallas, Texas: A Photographic Portrait'' (2007) [http://www.amazon.com/Dallas-Texas-Photographic-Peter-Calvin/dp/1885435754/ref=pd_bbs_sr_2?ie=UTF8&s=books&qid=1213913472&sr=1-2 excerpt and text search] | ||

* Fitzgerald, Ken. ''Dallas Then and Now'' (2001), 144pp; [http://www.amazon.com/Dallas-Then-Now/dp/1571454705/ref=pd_sim_b_1 excerpt and text search] | |||

* Hazel, Michael V. ''Dallas: A History of "Big D."'' (1997). 73 pp. | |||

* McDonald, . William L. ''Dallas Rediscovered: A Photographic Chronicle of Urban Expansion, 1870-1925'' (1978). | * McDonald, . William L. ''Dallas Rediscovered: A Photographic Chronicle of Urban Expansion, 1870-1925'' (1978). | ||

* Payne, Darwin. ''Dallas: An Illustrated History'' (1982). | * Payne, Darwin. ''Dallas: An Illustrated History'' (1982). | ||

| Line 17: | Line 38: | ||

* Rogers, John William. ''The Lusty Texans of Dallas'' (3rd ed. 1965) | * Rogers, John William. ''The Lusty Texans of Dallas'' (3rd ed. 1965) | ||

* WPA Writers' Program. ''The WPA Dallas Guide and History,'' ed. Maxine Holmes and Gerald D. Saxon (1939; 1992). | * WPA Writers' Program. ''The WPA Dallas Guide and History,'' ed. Maxine Holmes and Gerald D. Saxon (1939; 1992). | ||

===Specialized studies=== | |||

* Behnken, Brian D. "The 'Dallas Way': Protest, Response, and the Civil Rights Experience in Big D and Beyond." ''Southwestern Historical Quarterly'' 2007 111(1): 1-29. Issn: 0038-478x | |||

* Biderman, Rose G. "The Sanger Brothers and Their Role in Texas History." ''Western States Jewish History'' 1996 28(2): 149-158. Issn: 0749-5471 | |||

* Cristol, Gerry. ''A Light in the Prairie: Temple Emanu-El of Dallas, 1872-1997.'' (1998). 312 pp. | |||

* Decker, Stefanie. "Women in the Civil Rights Movement: Juanita Craft Versus the Dallas Elite." ''East Texas Historical Journal'' 2001 39(1): 33-42. Issn: 0424-1444 | |||

* Enstam, Elizabeth York. "The Dallas Equal Suffrage Association, Political Style, and Popular Culture: Grassroots Strategies of the Woman Suffrage Movement, 1913-1919." ''Journal of Southern History'' 2002 68(4): 817-848. Issn: 0022-4642 [http://www.questia.com/googleScholar.qst?docId=5002502597 online edition] | |||

* Enstam, Elizabeth York. ''Women and the Creation of Urban Life: Dallas, Texas, 1843-1920.'' (1998). 284 pp. | |||

* Fairbanks, Robert B. "Rethinking Urban Problems: Planning, Zoning, and City Government in Dallas, 1900-1930." ''Journal of Urban History'' 1999 25(6): 809-837. Issn: 0096-1442 Fulltext: [[Ebsco]] | |||

* Fairbanks, Robert B. ''For the City as a Whole: Planning, Politics, and the Public Interest in Dallas, Texas, 1900-1965.'' (1998). 318 pp. | |||

* Gower, Patricia E. "The Price of Exclusion: Dallas Municipal Policy and its Impact on African Americans." ''East Texas Historical Journal'' 2001 39(1): 43-54. Issn: 0424-1444 | |||

* Gower, Patricia Ellen. "Dallas: Experiments in Progressivism, 1898-1919." PhD dissertation Texas A. & M. U. 1996. 228 pp. DAI 1997 58(1): 263-A. DA9718350 Fulltext: [[ProQuest Dissertations & Theses]] | |||

* Hazel, Michael V., ed. ''Dallas Reconsidered: Essays in Local History'' (2000), 325pp | |||

* Hazel, Michael V. ''The Dallas Public Library: Celebrating a Century of Service, 1901-2001.'' (2001). 252 pp. | |||

* Hill, Patricia Evridge. ''Dallas: The Making of a Modern City.'' (1996). 240 pp. the standfard scholarly history | |||

* Hill-Aiello, Thomas A. "Dallas, Cotton and the Transatlantic Economy, 1885-1956." PhD dissertation U. of Texas, Arlington 2006. 326 pp. DAI 2007 67(9): 3555-A. DA3229563 Fulltext: [[ProQuest Dissertations & Theses]] | |||

* Linden, Glenn M. ''Desegregating Schools in Dallas.'' (1995). 243 pp. | |||

* McElhaney, Jacquelyn Masur. ''Pauline Periwinkle and Progressive Reform in Dallas.'' (1998). 201 pp. | |||

* Morgan, Ruth P. ''Governance by Decree: The Impact of the Voting Rights Act in Dallas.'' University Press of Kansas, 2004. 326 pp. | |||

* Ofman, May Walters. "The Practice of Social Welfare: A Case Study in Dallas, Texas, 1890-1929." PhD dissertation U. of Michigan 1999. 456 pp. DAI 2000 60(7): 2650-A. DA9938505 Fulltext: [[ProQuest Dissertations & Theses]] | |||

* Payne, Darwin. ''As Old as Dallas Itself: A History of Lawyers in Dallas, the Dallas Bar Associations, and the City They Helped Build.'' (1999). 325 pp. | |||

* Phillips, Michael. ''White Metropolis: Race, Ethnicity, and Religion in Dallas, 1841-2001.'' (2006). 300 pp. | |||

* Phillips, Michael. ''White Violence, Hegemony, and Slave Rebellion in Dallas, Texas, Before the Civil War.'' ''East Texas Historical Journal'' 1999 37(2): 25-35. Issn: 0424-1444 | |||

* Tatman, Arthur T. "La Camara, 1939: a 'Mexican; Chamber of Commerce Forms in Dallas.'' ''Journal of the West'' 2006 45(4): 36-47. Issn: 0022-5169 online at ABC-CLIO | |||

===Primary Sources=== | ===Primary Sources=== | ||

Revision as of 18:57, 19 June 2008

Dallas is a major city, county, and metropolitan area in northeastern Texas; the city population in 2006 was 1,250,180. The county population was 2,346,000 in 2000. The Dallas–Fort Worth–Arlington metropolitan area reached 6,145,000 million in 2007 after achieving the largest numeric gain of any metro area in the U.S. between 2006 and 2007, increasing by 162,250. Only New York, Los Angeles and Chicago metro areas were larger, while Houston came next after Dallas.

History

In 1841, two years after his first visit to stake a claim to the land on which Dallas now stands, John Neely Bryan, a Tennessee trader, returned to the then Republic of Texas and built a tiny one-room cabin, the first in Dallas. Ir remains one of the few historical landmarks preserved in the city, and has been moved to the front of the Dallas County Courthouse. Bryan, quick to see the advantages of the National Highway then being built toward his land, founded a village. In 1844 the village was laid out in lots 200 feet square. The only real clue as to the choice of the name for the village is a remark made by Bryan "I named it for my friend Dallas." Dallas County in 1846 was named after George Mifflin Dallas, the current vice-president of the United States. In 1852 Bryan sold his interest in the settlement to Alexander and Sarah Cockrell.

Dallas was incorporated as a town in 1856 and became an important rtegional trading center. In 1856 several hundred Europeans, followers of the French social philosopher Charles Fourier, attempted to set up a socialistic colony called "La Réunion" across the river from Dallas. The colony failed in 1858, and many of the colonists moved to Dallas, bringing with them a cosmopolitanism then lacking in most of the state.

The town, almost completely destroyed by fire in July 1860, was rebuilt during the 1860s. Phillips (1999) explores the economic, political, ethnic, and regional tensions that caused an outbreak of mass white hysteria in response to an alleged slave rebellion that was held responsible for the great fire. The fire destroyed the entire downtown and incited numerous hangings and torture of white Union sympathizers and blacks falsely accused of arson by the majority of pro-slavery Texans, such as rabid Confederate editor Charles R. Pryor of the Dallas Herald. These civil disturbances persisted despite pleas for justice by free-state whites living in Texas who hoped to minimize the vengeful mob mentality in the Dallas area.

During the Civil War, Dallas was the quartermaster, commissary, and administrative headquarters for the Confederate Army, but no fighting occurred near the city.

Dallas was incorporated as a city in 1871 and grew rapidly during the 1870s as a railroad and distribution center for northeast Texas. In 1873, through a trick played on the legislature, the east-west Texas and Pacific Railroad was persuaded to cross at Dallas the Houston and Texas tracks, which were being built northward from the Gulf. The boom years brought on by the railroad in the 1870s greatly accelerated the growth of Dallas while exacerbating class and ethnic stratification among the city's population.

By 1900 the city's population reached 38,000 and by 1930 it had risen to about 260,500.

Progressive era: 1890-1930

Progressive Era reformers sought to improve municipal government by such changes as the commission system, city planning, and zoning controls. The interests of white business and residential districts were protected, but sometimes at the expense of blacks who lived in segregated neighborhoods.[1] Fairbanks (1999) explores the changing assumptions about city planning and government among the city's leaders. Dissatisfied with its haphazard development they endorsed centralized planning and wrote and secured the adoption of a new charter and set up a board of commissioners. The commission structure, however, caused government officials to view the city in separate parts rather than as a whole. By the 1920s supporters of comprehensive planning were calling for a program that included adoption of council-manager government, a citywide zoning policy, and public funds for improvements in parks, sewers, schools, and city streets. Voters approved the bond proposals and charter amendments in 1927 and 1930. Dallas thus achieved a more coordinated government which was theoretically more aware of the city's needs and more able to treat those needs equally for the benefit of the city as a whole.

Self image

The city's fathers originally depicted Dallas as southern in order to rationalize slavery and opposition to Reconstruction, but this discouraged Northern investment and the political support of wealthy Yankee immigrants to the city. From the 1870s on, Dallas leaders portrayed the city as southwestern, or later as part of the "Sunbelt", in order to incorporate wealthy non-southern whites, including Jews, into society. For example, between 1852 and 1925 the seven Sanger brothers built successful mercantile businesses along developing railroad lines, including the Sanger Bros. department store, and occupied numerous city and state government posts.[2] White blue collar workers were marginalized, and even more so the Mexican Americans, and blacks.[3]

Gender

Women did much to establish the fundamental elements of the social structure of the city, focusing their energies on families, schools, and churches during the city's pioneer days. Many of the organizations which created a modern urban scene were founded and led by middle class women. Through voluntary organizations and club work, they connected their city to national cultural and social trends. By the 1880s women in temperance and suffrage movements shifted the boundaries between private and public life in Dallas by pushing their way into politics in the name of social issues.[4]

During 1913-19, advocates of woman suffrage drew on the educational and advertising techniques of the national parties and the lobbying tactics of the women's club movement. They also tapped into popular culture, successfully using popular symbolism and traditional ideals to adapt community festivals and social gatherings to the task of political persuasion. The Dallas Equal Suffrage Association developed a suffrage campaign based on social values and community standards. Community and social occasions served as recruiting opportunities for the suffrage cause, blunting its radical implications with the familiarity of customary events and dressing it in the values of traditional female behavior, especially propriety.[5]

Women of color usually operated separately. Juanita Craft (1902-85) was a leader in the civil rights movement through the Dallas NAACP. She focused on working with black youths, organizing them as the vanguard in protests against segregation practices in Texas.[6]

Bibliography

Guides and popular history

- Acheson, Sam Hanna. Dallas Yesterday, (1977)

- Buckner, Sharry. City Smart: Dallas/Ft. Worth (2000) excerpt and text search

- Calvin, Peter A. Dallas, Texas: A Photographic Portrait (2007) excerpt and text search

- Fitzgerald, Ken. Dallas Then and Now (2001), 144pp; excerpt and text search

- Hazel, Michael V. Dallas: A History of "Big D." (1997). 73 pp.

- McDonald, . William L. Dallas Rediscovered: A Photographic Chronicle of Urban Expansion, 1870-1925 (1978).

- Payne, Darwin. Dallas: An Illustrated History (1982).

- Rafferty, Robert R. Lone Star Guide to the Dallas/Fort Worth Metroplex, (2nd ed. 2003)

- Rogers, John William. The Lusty Texans of Dallas (3rd ed. 1965)

- WPA Writers' Program. The WPA Dallas Guide and History, ed. Maxine Holmes and Gerald D. Saxon (1939; 1992).

Specialized studies

- Behnken, Brian D. "The 'Dallas Way': Protest, Response, and the Civil Rights Experience in Big D and Beyond." Southwestern Historical Quarterly 2007 111(1): 1-29. Issn: 0038-478x

- Biderman, Rose G. "The Sanger Brothers and Their Role in Texas History." Western States Jewish History 1996 28(2): 149-158. Issn: 0749-5471

- Cristol, Gerry. A Light in the Prairie: Temple Emanu-El of Dallas, 1872-1997. (1998). 312 pp.

- Decker, Stefanie. "Women in the Civil Rights Movement: Juanita Craft Versus the Dallas Elite." East Texas Historical Journal 2001 39(1): 33-42. Issn: 0424-1444

- Enstam, Elizabeth York. "The Dallas Equal Suffrage Association, Political Style, and Popular Culture: Grassroots Strategies of the Woman Suffrage Movement, 1913-1919." Journal of Southern History 2002 68(4): 817-848. Issn: 0022-4642 online edition

- Enstam, Elizabeth York. Women and the Creation of Urban Life: Dallas, Texas, 1843-1920. (1998). 284 pp.

- Fairbanks, Robert B. "Rethinking Urban Problems: Planning, Zoning, and City Government in Dallas, 1900-1930." Journal of Urban History 1999 25(6): 809-837. Issn: 0096-1442 Fulltext: Ebsco

- Fairbanks, Robert B. For the City as a Whole: Planning, Politics, and the Public Interest in Dallas, Texas, 1900-1965. (1998). 318 pp.

- Gower, Patricia E. "The Price of Exclusion: Dallas Municipal Policy and its Impact on African Americans." East Texas Historical Journal 2001 39(1): 43-54. Issn: 0424-1444

- Gower, Patricia Ellen. "Dallas: Experiments in Progressivism, 1898-1919." PhD dissertation Texas A. & M. U. 1996. 228 pp. DAI 1997 58(1): 263-A. DA9718350 Fulltext: ProQuest Dissertations & Theses

- Hazel, Michael V., ed. Dallas Reconsidered: Essays in Local History (2000), 325pp

- Hazel, Michael V. The Dallas Public Library: Celebrating a Century of Service, 1901-2001. (2001). 252 pp.

- Hill, Patricia Evridge. Dallas: The Making of a Modern City. (1996). 240 pp. the standfard scholarly history

- Hill-Aiello, Thomas A. "Dallas, Cotton and the Transatlantic Economy, 1885-1956." PhD dissertation U. of Texas, Arlington 2006. 326 pp. DAI 2007 67(9): 3555-A. DA3229563 Fulltext: ProQuest Dissertations & Theses

- Linden, Glenn M. Desegregating Schools in Dallas. (1995). 243 pp.

- McElhaney, Jacquelyn Masur. Pauline Periwinkle and Progressive Reform in Dallas. (1998). 201 pp.

- Morgan, Ruth P. Governance by Decree: The Impact of the Voting Rights Act in Dallas. University Press of Kansas, 2004. 326 pp.

- Ofman, May Walters. "The Practice of Social Welfare: A Case Study in Dallas, Texas, 1890-1929." PhD dissertation U. of Michigan 1999. 456 pp. DAI 2000 60(7): 2650-A. DA9938505 Fulltext: ProQuest Dissertations & Theses

- Payne, Darwin. As Old as Dallas Itself: A History of Lawyers in Dallas, the Dallas Bar Associations, and the City They Helped Build. (1999). 325 pp.

- Phillips, Michael. White Metropolis: Race, Ethnicity, and Religion in Dallas, 1841-2001. (2006). 300 pp.

- Phillips, Michael. White Violence, Hegemony, and Slave Rebellion in Dallas, Texas, Before the Civil War. East Texas Historical Journal 1999 37(2): 25-35. Issn: 0424-1444

- Tatman, Arthur T. "La Camara, 1939: a 'Mexican; Chamber of Commerce Forms in Dallas. Journal of the West 2006 45(4): 36-47. Issn: 0022-5169 online at ABC-CLIO

Primary Sources

See also

Online resources

notes

- ↑ Patricia E. Gower, "The Price of Exclusion: Dallas Municipal Policy and its Impact on African Americans." East Texas Historical Journal 2001 39(1): 43-54. Issn: 0424-1444

- ↑ Rose G. Biderman, "The Sanger Brothers and Their Role in Texas History." Western States Jewish History 1996 28(2): 149-158. Issn: 0749-5471

- ↑ See Michael Phillips, White Metropolis: Race, Ethnicity, and Religion in Dallas, 1841-2001. (2006).

- ↑ Elizabeth York Enstam, Women and the Creation of Urban Life: Dallas, Texas, 1843-1920. (1998).

- ↑ Elizabeth York Enstam, "The Dallas Equal Suffrage Association, Political Style, and Popular Culture: Grassroots Strategies of the Woman Suffrage Movement, 1913-1919." Journal of Southern History 2002 68(4): 817-848.

- ↑ Stefanie Decker, "Women in the Civil Rights Movement: Juanita Craft Versus the Dallas Elite." East Texas Historical Journal 2001 39(1): 33-42. Issn: 0424-1444